From the Kennebec to the Huron

How One Black Family Learned to Move, Build, and Belong in Nineteenth-Century America

American history has a habit of fixing Black families in place, anchoring them to plantations, neighborhoods, or moments of trauma. Movement, when it appears, is often cast as flight rather than strategy. Yet for much of the nineteenth century, freedom for Black Americans did not come from staying put. It came from knowing when to move, how to move, and what to carry with you when you did.

The story of the Bow family unfolds across four borders and half a continent: from New England’s maritime towns to the gold fields of California, from exile in Canada to settlement in Ypsilanti. Their journey, carefully documented, strategically chosen, reveals a different architecture of Black agency. Long before the Great Migration reshaped American cities, the Bows had already mastered a politics of mobility, skilled labor, and institution-building that allowed them to claim citizenship on their own terms.

This is not a story of escape alone. It is a story of return.

Born Free, Carrying Bondage

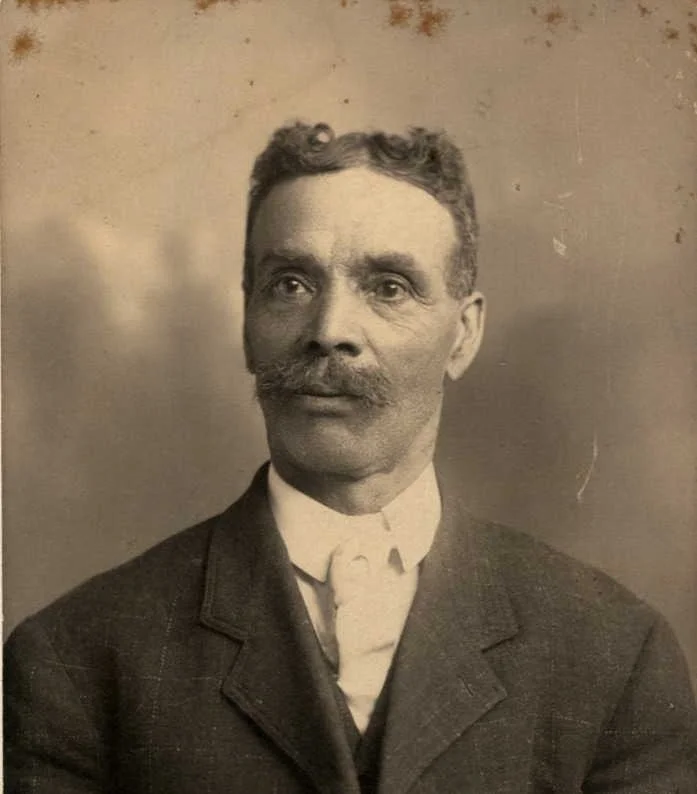

At the center of the Bow family history stands Christopher Egbert Bow, born around 1808. Later generations remembered him as a fugitive slave, someone who had “taken leg bail” from Maryland and run north. The phrase survived because it captured something emotionally true. Yet contemporary records from Maine insist on a quieter but more revealing distinction: Christopher Bow was born free, the child of parents who themselves had escaped slavery.

That difference matters. To be “free-born of slave parents” in the early nineteenth century was to live in a state of permanent contingency. Freedom was legal but fragile, documented but disputable. It meant understanding that any accusation could undo a life, that safety was temporary, and that vigilance, not law, was the real guarantor of survival.

For families like the Bows, freedom was not inherited as peace. It was inherited as responsibility.

The Atlantic World as Training Ground

Christopher’s marriage to Lydia Huston bound the family to a Black Atlantic culture shaped by seafaring, trade, and resistance. Lydia’s father, Francis Huston, was born in Nantucket in the mid-eighteenth century and survived repeated attempts to kidnap him into Southern slavery, an ever-present threat to free Black Northerners. Maritime life offered Huston something land rarely did: leverage. On ships, skill could outweigh color, and distance itself became protection.

By the 1830s, Christopher and Lydia Bow had settled in Brunswick, Maine, near the Kennebec River. There, Christopher farmed land and ran a teaming business, hauling goods with horses he owned outright. This was not subsistence work. Teaming required capital, reputation, and trust across racial lines. The local histories make a point of noting that Christopher “kept good horses,” a nineteenth-century shorthand for both economic standing and self-respect.

In a country that treated Black permanence as suspect, Christopher Bow built a life that was visible, solvent, and mobile all at once.

California and the Calculus of Risk

When gold was discovered in California in 1848, Christopher Bow joined the earliest wave heading west. For Black men, the journey carried extraordinary risk: exclusionary laws, racial violence, and the near certainty of exploitation. But it also offered something rare, liquid wealth, unbound to land or local prejudice.

Christopher ‘s decision to go west suggests that the family had already accumulated surplus capital. He could afford the journey. More telling still, he returned. Unlike many fortune-seekers who died or stayed, Christopher came back to Maine and resumed his business. The records suggest not failure, but consolidation. Whatever he gained, likely through supply hauling rather than mining itself, became portable capital.

That capital would soon matter more than land ever could.

Exile as Protection

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 transformed the legal geography of the United States. By empowering slave catchers, denying accused runaways the right to testify, and incentivizing kidnapping, the law rendered freedom provisional even in free states. For families like the Bows, whose freedom depended as much on memory as on paper, the risk was existential.

By the early 1860s, the Bow family left their Maine holdings and crossed into Canada West, settling near Chatham, Ontario. This was not panic. It was calculation.

Chatham had become a center of Black self-governance, a place where formerly enslaved people, free-born Northerners, and intellectual radicals built schools, farms, and churches. It hosted John Brown’s 1858 convention and served as a hub of abolitionist organizing. To live there was to inhabit a Black polity, protected by British law and animated by political purpose.

Exile, for the Bows, was not withdrawal. It was preparation.

Building a Transnational Community

In Canada, the Bow family forged lasting alliances. Their daughter Amelia married James Hill, a refugee from Kentucky. Their son Solomon married Elizabeth Richardson, a Canadian-born woman whose family had also navigated Underground Railroad routes. These unions bound together different strands of the Black North American experience, free-born New Englanders, formerly enslaved Southerners, and Canadian citizens, into a single kinship network.

This was a community fluent in borders. Movement was not disruption; it was inheritance.

Coming Back, On Their Own Terms

After the Civil War, thousands of Black Canadians returned south in what historians now call “reverse migration.” The Bow family was among them. They chose Ypsilanti, Michigan, a growing industrial town with antislavery roots and rail access linking Detroit and Chicago.

They did not arrive as isolated individuals. They arrived as a clan.

Parents, children, and in-laws settled within walking distance of one another, pooling labor, sharing childcare, and reinforcing economic stability. This proximity allowed something rare in post-war Black America: coordinated institution-building.

Carpentry as Power

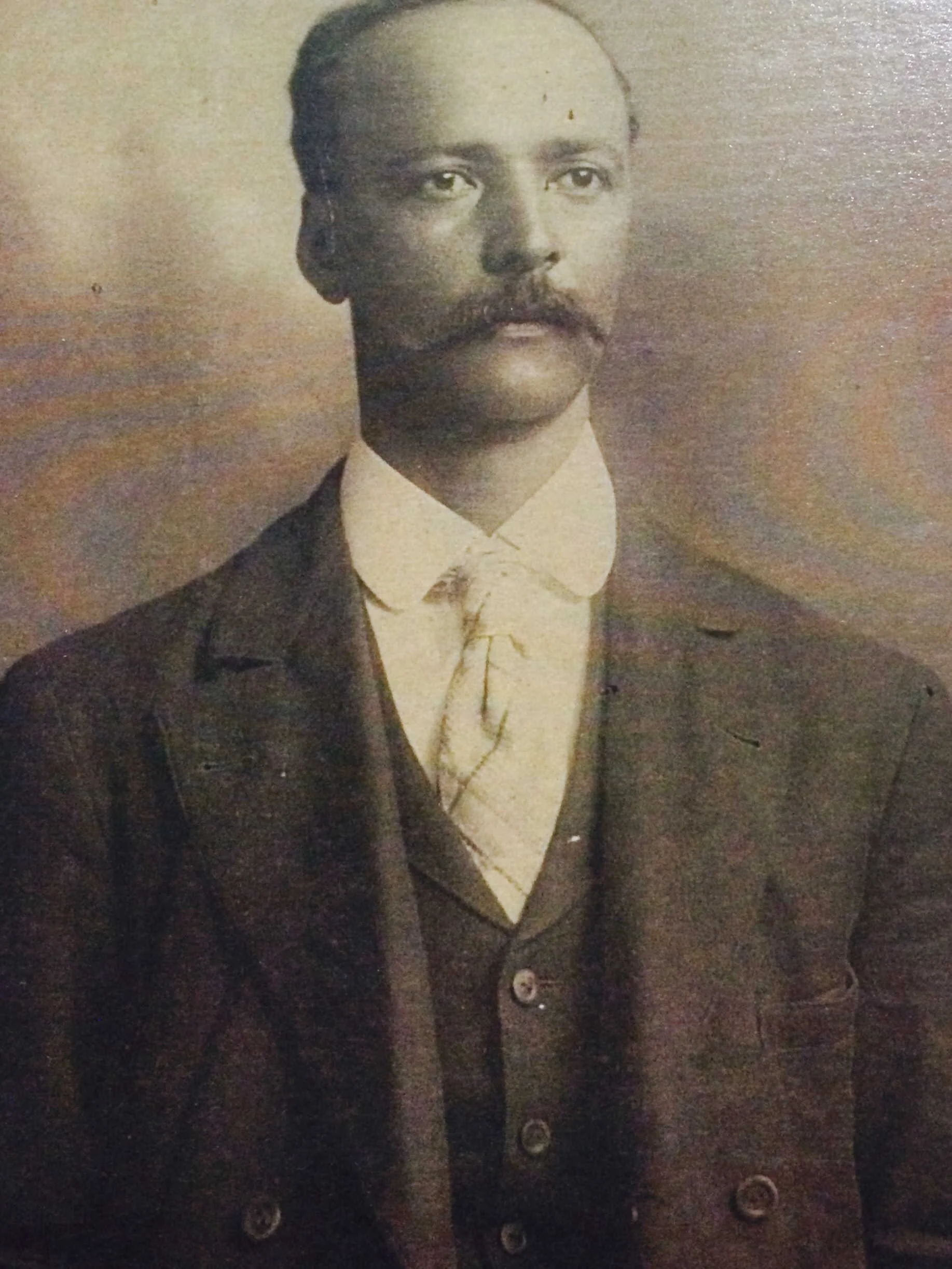

Solomon Bow emerged as a central figure in Black Ypsilanti. A master carpenter, he worked alongside other Canadian-returnee families, most notably the Kerseys, to build homes for Black residents at a time when white builders often refused such work.

Carpentry was not merely a trade. It was leverage. Skilled labor allowed Black builders to control pricing, timelines, and standards. It enabled Black homeownership, which in turn conferred stability, status, and political influence.

By the end of the nineteenth century, much of Black Ypsilanti’s housing stock bore the mark of Bow hands.

Building the Church, Building the Polis

The crown of this work was the construction of Brown African Methodist Episcopal Church. Designed by James Kersey and built by parishioners themselves, the church stood as more than a religious structure. The AME denomination, born from resistance to segregation, functioned as a political institution, a place where education, organizing, and strategy converged.

Speakers like Frances Ellen Watkins Harper passed through its doors. Suffrage, civil rights, and self-determination were debated beneath its rafters. To build an AME church was to declare permanence and autonomy in brick and timber.

For the Bows, faith and politics were never separate projects.

Politics With Consequences

Solomon Bow’s leadership extended beyond construction. In the 1870s, he led Ypsilanti’s Black Grant Club, an explicitly Republican organization committed to defending Reconstruction and the rights secured by the Civil War amendments.

These clubs were not symbolic. They were targets.

Newspaper accounts describe armed attacks on Black political meetings, with men beaten and pistols drawn. To organize publicly was to risk violence. Solomon did it anyway. The Grant Club met in schoolhouses, turning spaces of education into headquarters of resistance.

This courage was inherited. From Francis Huston’s resistance to kidnapping, to Christopher Bow’s flight to Canada, the family tradition was clear: freedom required action.

Memory, Truth, and the Meaning of “Leg Bail”

The persistent memory of Christopher Egbert Bow as a runaway slave, despite records of his free birth, reveals how Black families preserve truth. Oral history telescopes generations, compressing events to retain meaning rather than precision. Whether Christopher himself fled Maryland or inherited the story from parents who did, the lesson remained intact: safety was never guaranteed.

The family’s later flight to Canada reenacted that lesson. Memory became strategy.

A Pattern, Not an Exception

The Bow family’s story challenges the idea that Black progress arrived suddenly in the twentieth century. Long before factories beckoned Southern migrants north, families like the Bows had already built property-owning, politically active communities rooted in skill, faith, and mobility.

They moved when law turned hostile.

They learned trades that traveled.

They married across borders.

They built institutions before demanding recognition.

By the time the twentieth century arrived, Black Ypsilanti already possessed elders, homeowners, churches, and political veterans, not because freedom had been granted, but because it had been engineered.

The Bows did not wait for America to make room.

They built their own, and stepped into it.

Sources

Primary & Local Historical Sources

“305 Hill-Bow | South Adams Street @ 1900” – Family history, Bow migration, carpentry, and Black Ypsilanti community context.

South Adams Street @ 1900. https://southadamstreet1900.wordpress.com/305-hill-bow/ South Adams Street @ 1900Facts About Brunswick, Maine (1862) – Early account of Brunswick town history while Christopher Egbert Bow was alive; includes details about free Black residents. Curtis Memorial Library / Pejepscot Historical Society.

https://curtislibrary.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/furbish.htm Curtis Memorial LibraryHistory of Brunswick, Topsham, and Harpswell, Maine (1878) – Town history providing context for the Bow family’s early environment.

https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/towndocs/813 DigitalCommons@UMaineBrunswick, Maine — Local History & Genealogy Resources – Genealogy records, local newspaper archives, and cemetery indices useful for confirming family movement in Maine. Curtis Memorial Library.

https://curtislibrary.com/genealogy/local-history-resources/ Curtis Memorial Library

African American Community & Church History

5. Brown African Methodist Episcopal Church – South Adams Street @ 1900 – History of the AME congregation, its early worship spaces, and construction of the church by local Black builders.

https://southadamstreet1900.wordpress.com/brown-african-methodist-episcopal-church/ South Adams Street @ 1900

Brown Chapel AME Church (Official Church Site) – Contemporary church history page with historical roots of the congregation in Ypsilanti.

https://www.bcamecy.org/church-history bchapel“Michigan’s second-oldest AME church celebrates 180th anniversary in Ypsi” – News feature on the long history of Brown Chapel AME, including early founding and community role.

https://concentratemedia.com/brownchapel0688/ Concentrate

Oral & Community History

8. A.P. Marshall African American Oral History Archive (Ypsilanti District Library) – Interviews documenting Black life in Ypsilanti across generations; useful for contextual family and neighborhood history.

https://history.ypsilibrary.org/a-p-marshall-african-american-oral-history-archive/oral-histories/ Ypsilanti District Library Histories

Ypsilanti African American Interest Archives (A.P. Marshall Project) – Overview of the oral history project and its significance in preserving community memory.

https://www.ypsilibrary.org/interest/african-american-interest/ Ypsilanti District Library

Background Historical Context (Optional)

10. African Methodist Episcopal Church (Denomination History) – Broader historical context on the AME denomination’s origins and significance to Black autonomy and community organization.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/African_Methodist_Episcopal_Church Wikipedia

Brunswick, Maine – Town History Overview – Context for the Bow family’s early New England environment. Wikipedia entry.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brunswick%2C_Maine Wikipedia

How to Cite in Your Article (Suggested Format)

At the bottom of your piece you can present the sources like this:

Sources & Further Reading

“305 Hill-Bow | South Adams Street @ 1900,” South Adams Street @ 1900.

Facts About Brunswick, Maine (1862), Curtis Memorial Library.

History of Brunswick, Topsham, and Harpswell, Maine (1878).

Brown African Methodist Episcopal Church history, South Adams Street @ 1900.

Brown Chapel AME Church – Official Church History.

“Michigan’s second-oldest AME church celebrates 180th anniversary in Ypsi,” Concentrate Media.

A.P. Marshall African American Oral History Archive, Ypsilanti District Library.

African American Interest Archives, Ypsilanti District Library.

“African Methodist Episcopal Church” (denomination history).

“Brunswick, Maine,” Wikipedia (for town background).